by Paul Govern

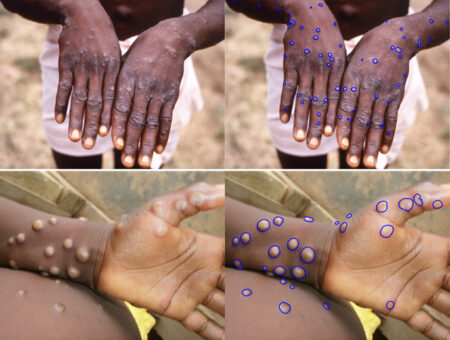

A machine learning algorithm developed by researchers at Vanderbilt University performs as well as humans at identifying skin lesions in clinical photographs of people with monkeypox.

The team’s report appeared Sept. 15 in the Journal of Investigative Dermatology.

The number of skin lesions an individual has is used by the World Health Organization as a primary measure of human monkeypox severity. Day-to-day change in amounts of lesions could be used to help assess patient responses in drug trials.

“In clinical trials of drugs that are being developed for monkeypox, if artificial intelligence operating on photographs could provide daily lesion counts, it could make the work far easier for everyone concerned. While our proof-of-concept study uses limited data, our results clearly demonstrate that an AI solution to speed intensive assessment of monkeypox severity is within reach,” said Eric Tkaczyk, MD, PhD, assistant professor of Dermatology, staff physician at the Department of Veterans Affairs and director of the Vanderbilt Dermatology Translational Research Clinic.

Monkeypox is endemic in tropical rainforest regions of Central and West Africa. Beginning in May, monkeypox outbreaks were reported for the first time in many regions outside of Africa. On Sept. 13, the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control reported a total of 19,379 cases since May in Europe, and on Sept. 14, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported 22,774 cases since May in the U.S., with 239 cases occurring in Tennessee. As of Sept. 14, the CDC had put the global case count at 59,606.

First described in 1958, the disease is mainly spread through intimate contact, typically skin to skin. Besides skin lesions, patients might experience fever, chills and other symptoms. The illness lasts two to four weeks, with most people infected in the current global outbreak recovering without the need for medical treatment. While fatalities from the globally spreading variant have been rare, with only one death reported in the U.S. and three deaths reported in Europe, higher fatality rates historically have been reported for people infected with a central Africa variant.

There is currently no specific drug treatment for monkeypox. According to the CDC website, “antiviral drugs and vaccines developed to protect against smallpox may be used to prevent and treat monkeypox virus infections.” For more on monkeypox, including prevention, see the CDC website.

Tkaczyk led the machine learning study with Andrew McNeil, PhD, a post-doctoral fellow in Electrical and Computer Engineering, Inga Saknite, adjoint assistant professor of Dermatology, and Benoit Dawant, PhD, Cornelius Vanderbilt Professor of Engineering and director of the Vanderbilt Institute for Surgery and Engineering.

“This is a good example of what’s possible when researchers from Vanderbilt’s schools of engineering and medicine are able to pool their expertise,” Dawant said.

The project leveraged 66 photographs of 18 patients from an observational study in the Democratic Republic of Congo. On each image, a team member marked borders around lesions, providing training data for machine learning. In testing on photos withheld from the training step, lesion counts by the machine learning algorithm were on par with counts by two human raters.

Others on the study from VUMC include David House and Ziche Chen. The team included researchers from the Institut National de Recherche Biomédicale in the Democratic Republic of Congo, the Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research, and the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The study was supported by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, the European Regional Development Fund and the NIH (CA090625, AR074589).

For more on use of the machine learning algorithm in drug testing, see the story from Vanderbilt University Research News.